- Home

- About AALHE

- Board of Directors

- Committees

- Guiding Documents

- Legal Information

- Organizational Chart

- Our Institutional Partners

- Membership Benefits

- Member Spotlight

- Contact Us

- Member Home

- Symposium

- Annual Conference

- Resources

- Publications

- Donate

EMERGING DIALOGUES IN ASSESSMENTSuccessful Implementation of an Alternative Reporting Cycle to Seek Student Learning Improvement

September 25, 2025

AbstractIn assessing program-level student learning outcomes, many higher education institutions utilize a cycle in which faculty provide data analyses and plans to improve student learning on an annual basis. However, this process can pose challenges for both faculty and assessment staff. To address these challenges, one institution recently implemented a triennial assessment reporting process; as the name suggests, programs submit detailed reports once every three years. This article provides an overview of the process and implementation, including insights gained so far and future directions.

In the world of academic program assessment, there is a commonality to the cycles utilized by assessment offices at higher education institutions. The number and naming of the steps can vary, but the process is the same: program faculty determine student learning outcomes, collect data about student learning as they make their way through the curriculum, and use that information to determine not only how well outcomes were met, but where student learning could be improved moving forward. Using data for continuous improvement is considered essential enough that institutional and programmatic accreditors have incorporated it into their standards. For example, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (2024) standard 8.2.a and Higher Learning Commission (2024) standard 3.E both explain the requirement for all academic programs to regularly assess student learning outcomes and utilize the data to seek improvement. At the program level, an example can be found with ABET (2023) criterion 4 for the accreditation of computing programs. It specifies the necessity of using results from the assessment of student learning outcomes in the program’s continuous improvement plans. This is not an exhaustive list, but illustrates that accreditors consider seeking student learning improvement to be a key component of academic program quality. When it comes to the frequency of assessment reporting, there is no exact statistic to be found on cycle length. However, it is not uncommon within accreditation reports, assessment journals, and assessment conferences for institutions to describe an annual process. As the name suggests, programs submit reports filled with detailed analyses and plans to seek improvement in student learning each year. The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, starting from scratch with program assessment, implemented its version of an annual reporting process in the 2012-2013 academic year. Though the process had its benefits (e.g., solidified a culture of assessment, provided more frequent evidence for accreditation reports), it became clear over the years that it also presented two key challenges:

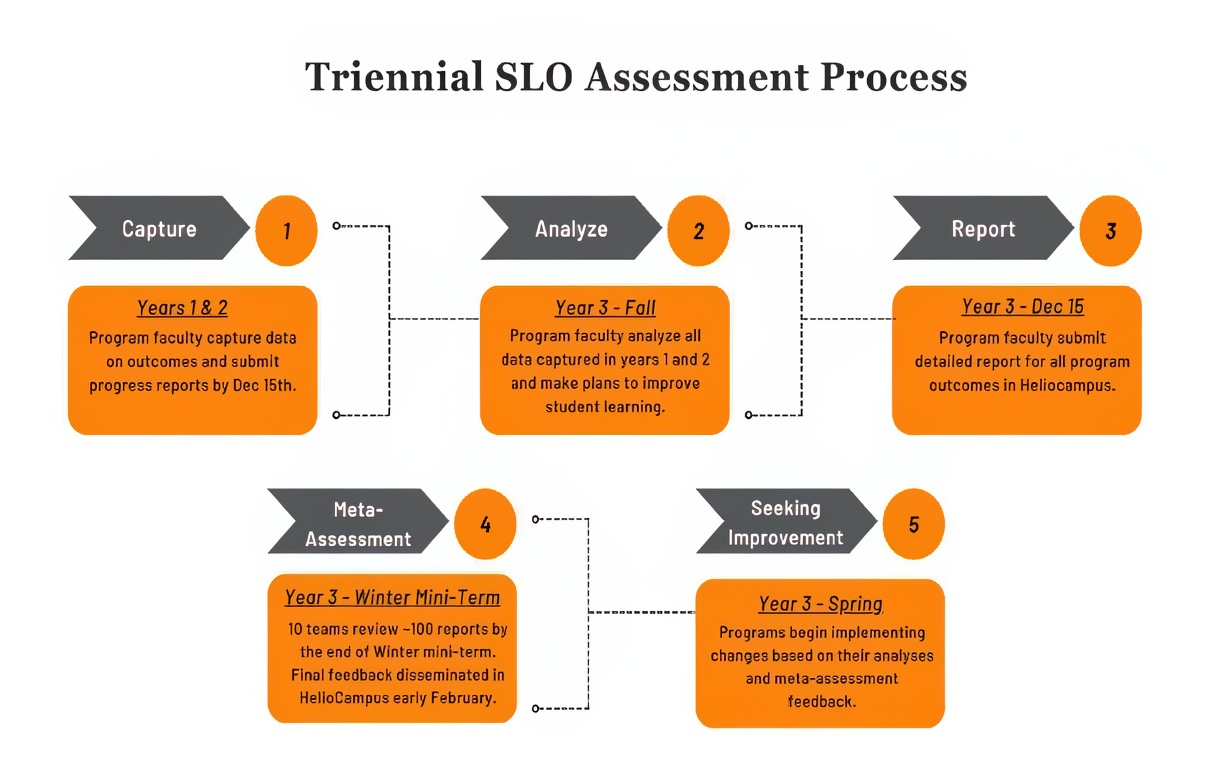

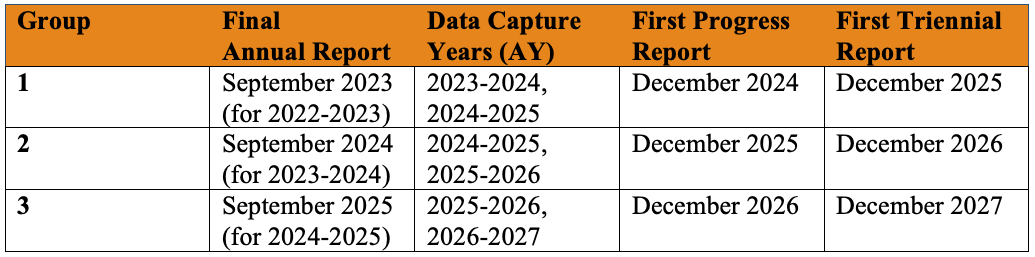

Given these challenges, the university’s Assessment Steering Committee (ASC) began exploring alternative reporting cycles in the Summer of 2023. After discussing options, the decision was made to implement a triennial reporting cycle. As the name suggests, programs submit a full, detailed report once every three years instead of every year. This does not mean, however, that they are free from reporting anything in those first two years; in lieu of a full report, programs submit brief updates (i.e., progress reports) on their assessment activities for the academic year (e.g., description of data captured, if any actions to seek student learning improvement were implemented, etc.). The key difference is that no analyses or new plans to seek improvement are required in the progress reports. Overall, this process allows programs to spend more time capturing and reflecting on data. Additionally, programs are divided into three groups (i.e., cohorts) so that in any given year, only a third of programs submit full reports. This makes the process more manageable for assessment staff. Notably, colleges were kept together, as splitting them up would have caused considerable challenges in keeping implementation timelines in order. The triennial cycle is not an entirely novel approach, as Christopher Newport University (CNU) implemented a triennial cycle in the 2014-2015 academic year (Lyons & Polychronopoulos, 2018). As such, UTK staff discussed the implementation with CNU and proceeded to plan an adaptation of that process. Iterations were passed through the Assessment Steering Committee, Academic Assessment Council, various faculty who had experience in writing and/or reviewing annual assessment reports, and a consultant affiliated with the regional accreditor before a final version was enacted. Steps within this new cycle can be found in the graphic below. RolloutTo roll out the process, a series of informational sessions were held by the ASC for each group of programs. Four in-person and two Zoom sessions were offered for each group, totaling six options for participants to choose from. Invitees consisted of report writers, department heads, and assistant/associate deans for academic affairs. Though report writers carry the responsibility of ensuring information is submitted, the ASC considered it essential that department and college-level leadership was included as well. As a result, each group consisted of 80-100 invitees. Sessions covered the rationale behind the transition from annual to triennial reporting, what the transition timeline was for their respective group, and future timelines. With three groups, the transition is staggered. The table below shows the implementation timeline for each group: Challenge of ImplementationThe main challenge in the implementation was the adjustment of reporting deadlines. This manifested itself in two ways: First, the annual cycle reports were due by September 22nd for the previous academic year. With the triennial cycle, programs spend two academic years capturing data and submit a report by the end of the fall semester of the third year (December 15th). Because the institution did not wish to have different deadlines for progress reports vs full reports, progress reports are due by December 15th as well. To avoid having programs submit their last annual report in September and a triennial progress report just 3 months later, programs submit only one progress report in their first triennial cycle. For example, the first group submitted their last annual reports in September 2023 and then submitted a progress report in December of 2024. They will submit their first triennial report in December 2025 that features analyses on data collected in AY 2023-2024 and AY 2024-2025. After that, they will be in the cycle of 2 progress reports (December 2026 and 2027) before their next triennial report (December 2028) is due. This has caused slight confusion amid implementation but has been quickly resolved by proactive reminders and frequent conversations with programs. Second, a small number of faculty initially struggled with the shift in deadlines. Primarily, they cited the end-of-semester workload of submitting final course grades and mid-year graduation activities as challenges in meeting the deadline. These concerns have been alleviated by opening the report template several months before the deadline, allowing programs to submit the report earlier if they choose to do so. Current StatusAs referenced earlier, Group 1 submitted their first progress reports in December 2024. The template was built and launched within the university’s assessment management system in Summer 2024, giving programs several months to familiarize themselves with the template. Additionally, the ASC provided examples of progress reports to guide their efforts. As the deadline approached, frequent reminders were issued, and assistance was offered from the Assessment Steering Committee via email and drop-in help sessions in finalizing reports. As a result, 92 out of 99 reports were submitted by the deadline. A further four reports were submitted within a few days after, leaving only a handful that had to be “chased down.” This is considered a satisfactory result, particularly given that the process was so new. When the template was created, an option at the end of the form asked programs if they wanted an assessment consultation. This was part of the efforts for assessment staff to become more proactive in their assessment approaches. Eleven programs selected yes to that option, and thus part of the Spring 2025 semester was spent following up with those programs. Moving ForwardIn Spring 2025, report preview sessions were offered to each group that were tailored to where they were within the new cycle. Group 1 was guided through the full triennial report template, as it featured a significant overhaul from the previous annual report template. Group 2 was shown the progress report template and examples, and Group 3 was offered sessions to assist them with wrapping up their last annual reports and entering the triennial cycle on solid footing. Proactive efforts will certainly not end there. After all groups have transitioned, there will still be assistance provided to keep programs on track and incorporate new programs into the process. However, it’s expected that most programs will settle into a groove and need less frequent reminders about reporting deadlines and how the triennial cycle operates. This will allow assessment staff to have more in-depth conversations with programs when it comes to fully leveraging assessment data. ReceptionThough it is a major adjustment, programs have been thrilled with the change in the reporting cycle. Faculty have repeatedly stated that they appreciate having more time to capture and reflect on data, as well as having more time to enact plans to seek student learning improvement before the next full report is due. This is terrific feedback, and the university will continue to build on this in the future by seeking more formal feedback (both quantitative and qualitative) once all groups have fully transitioned to the triennial cycle. It is the institution’s hope to show other institutions that alternative reporting cycles can still accomplish the important work of collecting information about student learning and seeking ways to improve it. ReferencesABET. (2023). 2024–2025 Criteria for accrediting computing programs. Computing Accreditation Commission. https://www.abet.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/2024-2025_CAC_Criteria.pdf Higher Learning Commission. (2024). Criteria for accreditation and assumed practices (Revised June 2024). https://download.hlcommission.org/policy/updates/AdoptedPolicy-Criteria_2024-06_POL.pdf Lyons, J., & Polychronopoulos, G. (2018). Triennial assessment as an alternative to annual assessment. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois and Indiana University, National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment (NILOA). Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges. (2024). The principles of accreditation: Foundations for quality enhancement (2024 ed.). https://sacscoc.org/app/uploads/2024/01/2024PrinciplesOfAccreditation.pdf SACSCOC+9 |